Beethoven interpretations

Paul Wells lists and ranks a half-dozen boxed sets of the Beethoven symphonies, which brings up a point that I’ve only recently figured out: it is not only permissible to have more than one recording of a work of classical music, it can also be desirable to listen to different interpretations of the same work.

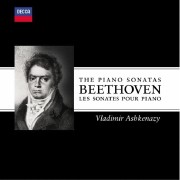

The more I learn about classical music, the more I realize how much this is true. I recently picked up a 10-disc boxed set of the Beethoven piano sonatas performed by Vladimir Ashkenazy; at less than $40, it’s hella cheap, like the Zinman Beethoven symphonies that Wells touts. I’d previously been collecting the John O’Conor performances on Telarc, but they’re now hard to find and I can’t complete the set. Which is a pity: O’Conor appears to be a Beethoven specialist, whereas many other performers recording the sonatas seem to be Romantic specalists like Ashkenazy for whom Beethoven is not the primary focus of their careers.

The more I learn about classical music, the more I realize how much this is true. I recently picked up a 10-disc boxed set of the Beethoven piano sonatas performed by Vladimir Ashkenazy; at less than $40, it’s hella cheap, like the Zinman Beethoven symphonies that Wells touts. I’d previously been collecting the John O’Conor performances on Telarc, but they’re now hard to find and I can’t complete the set. Which is a pity: O’Conor appears to be a Beethoven specialist, whereas many other performers recording the sonatas seem to be Romantic specalists like Ashkenazy for whom Beethoven is not the primary focus of their careers.

On balance, I think I prefer O’Conor’s interpretation to Ashkenazy’s. O’Conor is crisper and faster: for example, he plays the second movement of Opus 28 (Piano Sonata No. 15 in D major) in 5:47, whereas Ashkenazy takes more than eight languourous minutes. It’s not consistent: sometimes O’Conor is legato where Ashkenazy is staccato; sometimes it’s vice versa. These are, of course, interpretations: they’re making decisions about how to play these pieces. As I learn more about the sonatas (which, by the way, are my passion and my life and my favouritest music ever), as I pore over the scores and read books like Charles Rosen’s (Amazon.com, Amazon.ca), I notice where those decisions are being made. I hope that at some point I’ll have learned enough to understand why they’re being made.

In the meantime, though, I’m giving myself permission to buy more music.